16.04.2024 by Anastasia Ruvimova

Envisioning the VR-Powered Office of the Future

Could Virtual Reality (VR) create a better environment for workers trying to be productive and focused in their home office? Read further about our week-long field study with software developers using VR for working from home.

Rethinking the Future of Work

With many companies shifting from on-site work to remote or hybrid policies (a movement catalysed by the COVID-19 pandemic), there is a growing interest to understand how technology can assist remote knowledge workers, especially in the unique set of challenges that a home environment imposes. The lines between home and work spheres are increasingly blurred. For many, remote work happens from the bedroom or shared spaces such as the kitchen, where environmental cues and potentially household members in our peripheral vision make it difficult to give full attention to the task at hand. How can we help workers enter the right mental state for concentrated work, even from the confines of their home?

To inform and motivate this work, our collaborators at Virginia Commonwealth University (lead by Fronchetti and Shepherd) first investigated the problems people currently face in their home offices. They conducted a digital ethnography on a dataset of images sampled from three subreddits where users share and comment on the workstations they’ve created for their home: r/Battlestations, r/Workstations, and r/Workspaces. An analysis of these photos illuminated some problems frequent in people’s home workspaces. Common issues included: limited desk space (66% of instances), backlit or sidelit (37%), clutter (8%), working from a common space of the home (such as a dining table) (7%), presence of pets (4%), working from the bedroom (3%), and sharing the space with another person (2%). Many of these issues cause visual distraction for the worker. Could VR help alleviate these?

Enter Virtual Reality

As VR technology continually advances – with the steady release of higher-resolution, more comfortable headsets – an enticing question is whether VR could be effective for regular seated office work. On first encounter, the idea might sound like it comes straight out of an Ernest Cline novel – but when considering the possibilities VR technology offers, this notion may not be so farfetched. Head-mounted displays offer the dual benefit of blocking out the user’s immediate environment (with all its distractions) while replacing it with a virtual background of choice – imagine the serenity of an alpine forest or a starry sky.

The sedentary nature of office work lends itself well to VR for three reasons:

- it requires only a simple hardware setup (the base stations need only to cover the user’s desk area),

- the user can use a wired headset, which allows for greater graphics performance than wireless ones, and

- the risk of motion sickness is low(er) compared to activities where the user and/or virtual world are in active motion (the mismatch between the user’s actual movements and vision is the main culprit, which explains why motion sickness often dampens experiences of motion-heavy virtual activities such as video games and flight simulators).

It seems that everything is set for trying out VR office work for real.

Image Source: Pexels

A sample of images from the dataset showing a cluttered workspace.

16.04.2024 by Anastasia Ruvimova

Putting VR to the Test

Research in this area is still relatively new and incomplete. Past studies, including our lab’s 2020 exploration of VR in open offices, largely took place in controlled lab environments with carefully designed tasks. But what is working in VR really like, for real workers working from real homes on real tasks?

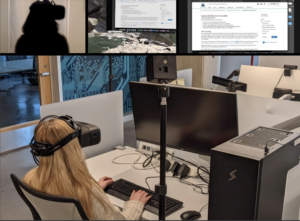

We designed a case study with 10 software developers, asking them to work for two to three hours a day in a VR headset, performing their actual work and breaks as they normally would. We kept the configuration as close as possible a normal office setup – with a traditional keyboard and mouse, which users could see through a pass-through window when they tilted their head down.

Findings

Participants reported several focus-inducing effects of doing work in VR, such as being less:

- distracted,

- drawn towards checking their phones, and

- aware of others in their space (for better or worse).

Participants also mentioned boosts in mood, such as from enjoying the nature surroundings and virtual sunlight which replaced, for some, fluorescent lighting indoors or gray weather outside.

The virtual screen also provided some ergonomic advantages in enlarging the user’s workspace, which meant less scrolling or switching between windows. At the same time, there were some drawbacks: the headset was too heavy and the chord often got in the way, it was difficult to interact with the physical space (e.g. when typing or drinking). It was also difficult or awkward to interact with household members. In the words of one participant,

“There’s a part where my husband comes in and actually like scares the crap out of me. ‘Cause I didn’t hear him come in. He laughed like hysterically for five minutes” (P08).

It was curious to see unexpected ways in which participants used the camera pass-through feature, which was intended to help typing and mouse-usage tasks. Though many participants mentioned reduced phone usage whilst in VR, we saw one participant actually texting on their phone using the pass-through. A couple other participants mentioned the feature’s usefulness for interacting with their pets:

“If I hear the cat around me, I used [the pass-through feature] so I wasn’t going to like accidentally punch her while trying to reach for the mouse” (P07)

Another participant even used it to sneak their dog treats while in VR. Its a nod to how users can adapt the technology to serve their individual needs.

Long Term Adoption

When asked what would be required before the participant could envision working in VR regularly, common requests included:

- having a lighter, chordless, more comfortable headset,

- more than one window projected into the space, and

- more choices of virtual environments to suit the user’s style (e.g. more minimalist or more stimulating)

We learned that working in VR offers potential benefits for focus and mood, but that a number of ergonomic challenges need to be addressed first. Due to some of the known effects of long-immersion effect (such as nausea or eye strain), we suggest that VR might be better suited for dedicated moments of focus time, when the user wishes to escape their current space and transport into one more conducive to their wellbeing and productivity.

We invite you to read further in our publication.

Experimental setup, including a view of the data-capture at the top: webcam, in-VR view, and screen recording.

A participant tries to take a drink while in VR. The shape of the headset makes this act difficult, speaking to a need for ergonomic solutions before users can adopt VR for long immersion.

A participant uses the pass-through to give their dog treats.